Archive for the ‘Translation’ Category

Nadja in French, and Nadja in English

It is a well-known fact of course that something gets lost when you read a work in translation, but sometimes the loss can be greater than expected. Take André Breton’s Nadja, for instance. To the best of my knowledge, the only English translation available is the one by Richard Howard. It was initially published in 1960 and is still published today by, I think, at least two publishers: Penguin and Atlantic Books. The Penguin edition (pictured below right) dates from 1999 and includes an introduction by Mark Polizzotti. Howard’s translation, however, is of the first edition of Nadja, which was published in 1928, long before Breton brought out his second, revised edition in 1964. Strangely enough, this fact is not mentioned on the front or back covers of the Penguin edition, although Polizzotti does mention it in his introduction, albeit in a footnote. I haven’t ever read the two works closely, but the second edition notably includes an “avant-dire”, a preface of sorts, in which Breton evokes his use of photographic illustrations in the book, of which there are indeed more in the later edition.

The Craft of Translation

Edited by John Biguenet and Rainer Schulte, The Craft of Translation is a collection of essays on literary translation that covers a wide range of texts (theatre, fiction, poetry, epic) over a long period of time (from the eleventh to the twentieth centuries) and a no less vast range of countries (from South America to Japan).

The essays were all written by literary translators who have tackled major writers past and present, and although not all their names may be familiar, some at least are worth mentioning alongside some of the authors they have worked on: Gregory Rabassa – Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargos Llosa, Juan Goytisolo; Margaret Sayers Peden – Isabel Allende, Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes; Donald Frame – Voltaire and Molière; William Weaver – Italo Calvino, Alberto Moravia, Primo Levi; Christopher Middleton – Goethe, Nietzsche, Robert Walser, Paul Celan; Edward Seidensticker – Lady Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji.

The volume is interesting because it gives a quite detailed and well-illustrated overview of the translation process in practice. And indeed, despite the differences in genre and source language, the volume is quite coherent, since all these translators face a number of similar problems, such as how to convey the sounds of a particular language, or how to translate curses and oaths, or how to render local expression and idiom in English. The risks involved in collaborative translations are also evoked by one essayist, who notes that his Americanisms did not mix well with the Britishisms of his fellow translator. The question is also raised by a translator of poetry as to whether his voice should show or, on the contrary, be mute. This issue ties in with the question as to the extent to which the translator should retain a sense of differentness in his translation. Last but not least, the very issue of translatability is raised repeatedly: while one essayist calculates the relative feasibility of a translation before starting on a job, another suggests that the translation of a poem should always be followed by a blank page for the ideal translation, which, of course, always remains out of reach.

Published in 1989 by the University of Chicago Press in their series “Guides to Writing, Editing and Publishing”, this volume is labelled “Reference / Literary Criticism”, and quite rightly so. Indeed, it emerges clearly from these essays that these translators are engaged in literary interpretation that is far from superficial, and their readings of the original works can teach us much.

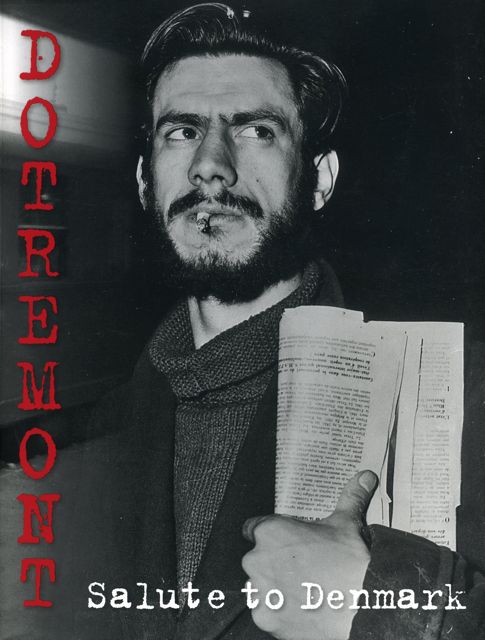

Christian Dotremont’s Salute to Denmark

An exhibition on the work of the Belgian poet and artist Christian Dotremont (1922-1979) opens today, 28 October 2011, at the Carl-Henning Pedersen & Else Alfelts Museum in Herning, Denmark. Dotremont, one of the founders of Cobra and the driving force behind the group, was drawn to Denmark from a very young age and visited the country many times during his lifetime. He first went there in 1948 with the Danish painter Asger Jorn, with whom he created the first word-paintings. Dotremont would later create his famous logograms.

The exhibition runs until 26 February 2012. The catalogue, pictured below, includes my translations (from French) of the article “Dotremont in the Land of Nja” and of the biography. I also translated titles of his works and other short texts used in the exhibition.

J.M. Coetzee, writer and translator

I think it’s fair to say that the (two-time) Booker Prize-winner and (one-time) Nobel Prize-winner J.M. Coetzee is better known for his novels and essays than for his translations. In fact, I’m not even really sure I knew that Coetzee had done some translations until I discovered one of these works quite by a chance in a second-hand bookshop some time ago.

The book in question is A Posthumous Confession, a translation – “from the Netherlandic”, readers are told – of Een nagelaten bekentenis (1896), by the Dutch novelist Marcellus Emants (1848-1923). Coetzee’s translation was released in 1975 as volume 7 in the quaintly named “Library of Netherlandic Literature” edited by the no less quaintly named Egbert Krispyn and published by Twayne: Coetzee’s name is visible in the bottom right-hand corner of the front cover (pictured below left). By a strange coincidence, I see that the novel was reissued earlier this year by New York Review Books, with an introduction by Coetzee, dating, however, from the mid eighties (pictured below right).

A Posthumous Confession is not Coetzee’s only translation. He has also translated from Afrikaans The Expedition to the Baobab Tree by Wilma Stockenström: it was first published by Jonathan Ball in Johannesburg in 1983 and by Faber in London in 1984. It was reissued by the South African publisher Human & Rousseau in March of last year. And in 2003, Coetzee brought out a volume of Dutch poetry, Landscape with Rowers: Poetry from the Netherlands, in a bilingual edition published by Princeton University Press.

For readers who are well acquainted with Coetzee’s fiction and who have enough knowledge of Dutch (and perhaps Afrikaans) to read these works in the original, it must be interesting to go over his translations to try to discover stylistic and perhaps thematic overlappings between his own work as a novelist and the works he chose to translate. Indeed, more so than in any other type of translation, here readers really are left wondering who they are in fact reading, whose voice it is they are listening to, whether that of the original author, or that of the translator.

The art of “artspeak” and “artspoke” (but not in French)

There are times when, as a translator, you have to recognize that certain terms or expressions just cannot be translated from one language into another. And I think it takes a good translator to know when to throw in the towel. Here’s an example from an English to French translation.

The American writer, art historian and journalist Robert Atkins is the author, among others, of two useful guides to the field of art and art history and to the field’s particular lingo or jargon. The first of these volumes, published in 1993, was titled ArtSpoke: A Guide to Modern Ideas, Movements and Buzzwords, 1848-1944, while the second, published in 1997, was titled ArtSpeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements and Buzzwords, 1945 to the Present.

The difficulty for a translator in this case, of course, lies in translating “artspoke” and “artspeak”. “Art-spoke” is the simple past, as it were, of “art-speak”, and the term can only really exist, and be understood, in relation to the latter. “Artspeak” was formed, it seems, on the pattern of “Newspeak”, the artificial language used in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. “Artspeak”, then, hints at the impenetrable obscurity of this critical jargon while also promising, as the title of the volume, to shed light on it.

So how is one to translate these terms into French? Well, one possibility, for “artspeak”, would be to do so on the pattern of the French translation of “Newspeak” (the dreadful “novlangue”). But “art-langue” or something similar would not only be meaningless but also sounds quite ridiculous, besides failing to capture the contrived nature of the term. Needless to say, conjugating that term to arrive at an equivalent of “art-spoke” seems virtually impossible.

The translator of these volumes, Jeanne Bouniort, thus rightly chose to drop “Artspoke” and “Artspeak” from the titles, and to opt for broader, though also more concise titles: Petit lexique de l’art moderne, 1848-1945 (2000), and Petit lexique de l’art contemporain (1998). And in fact, the French editions are presented as French “versions” of the English text, and quite rightly so, too. Both the English and French editions are published by Abbeville Press, which specializes in fine art and illustrated books.

Inspector, Detective, or Superintendent Maigret?

In 1950, five years after moving to the United States in 1945, Georges Simenon, having learned enough English, started paying attention to the English translations of his novels.

The first thing Simenon wanted to know was what to call his famous “commissaire”, Maigret: should it be “inspector”, as Simenon suggested, “superintendent” as his translator preferred, or should it be “detective” in the hope of satisfying both the English and the Americans? We know what was chosen – “inspector” – but this is an example of what translation is all about: choosing the right term to express the original.

The above anecdote is from Pierre Assouline’s biography, Simenon, featured below in a 1996 edition published by Folio Gallimard. (Strangely enough, the English translations of this edition are less than half the length in page numbers of the French edition.)