Grand Hotel Europa, a tribute to literary translators

A lot of people were at the Flagey arts centre in Brussels this past Friday for Grand Hotel Europa, a tribute to literary translators organized by the European Platform for Literary Translation PETRA. And although I’m not a literary translator, I was one of those attending the event.

The evening started with a panel discussion featuring the Croatian writer Dubravka Ugresic, the Japanese-to-Dutch translator Luk van Haute, and the Arabic-to-English translator and researcher Alice Guthrie. They discussed various aspects of translation, from the changes made by translators to the original and the differences between “big” and “small” languages with regards to the book market. It was an interesting warm-up to the main event, which was held in the main hall.

The main event began with a brief talk entitled “Found in Translation” by the American writer Michael Cunningham, who talked of the writer, translator and reader each as translators in their own right: the writer translating his ideas into words, the translator turning one language into another, and readers each translating the words into their own mental images. Cunningham’s talk was followed by a live translation into three languages (French, Dutch, and a third one I couldn’t recognize) of a short text from Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet: their translations were shown live on a big screen in real time, and it was interesting and amusing seeing the differences in their approaches, even on such a short text. Alberto Manguel then gave a talk entitled “Translation: A Miracle” in which he gave an overview of translation in South America from La Malinche (who acted as Cortes’s translator in the early 16th century) until today. Dubravka Ugresic, a Croatian writer living in the Netherlands, finished off the evening with a talk entitled “Out of Nation Zone”, a witty and perceptive view of translation from the perspective of a woman writing in a “small” language. I left Flagey with some food for thought.

David Bellos on translation

Published a few months ago, David Bellos’s Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything (Particular Books, 2011) has received what must be considerable attention for a book on translation, and what’s more, the attention has, to the best of my knowledge, been overwhelmingly positive.

In this book, Bellos – the translator of Georges Perec and Romain Gary among others, and a professor of literature at Princeton – sets out, neither to tell readers how to translate or how he translates nor to tell us what translation is, but to understand “what translation does“. His is a bold attempt to paint a big picture, he says, by exploring “the role of translation in cultural, social and human issues of many kinds”.

It is indeed, as the subtitle suggests somewhat vaguely, an ambitious book. Bellos discusses and occasionally quotes from a wide range of languages, so wide a range, in fact, that one wonders how many of these languages Bellos actually really knows and how in turn he can write about them and their translations if he does not: from French to Finnish, from Chinese to Hebrew, from German to Turkish, from Latin to Tok Pisin which, you’ll be happy to learn, is the lingua franca of Papua New Guinea. I, for one, would not feel comfortable discussing them second-hand.

Besides the vast range of languages, Bellos also covers a wide range of topics touching on translation, but also on language and communication more generally: from comic strips to film subtitles, from computer-aided translation to the translation of legalese, from literary translation to the translation of humour, from the translation of news to that of the Bible. And the list does not stop there.

The book has 32 chapters spread out over some 340 pages, which gives little room to develop any of these topics in any detail. And that’s very much part of the problem: by choosing to cover so much, Bellos ultimately fails to cover anything satisfactorily. Hence the feeling also that the book is generally anecdotal, and that Bellos is more concerned with telling little anecdotes or stories. And this in turn is a pity since many of the topics he touches on are interesting in themselves, but dealt with too superficially. And it’s also a pity because he has translated many books by Perec and Gary as well as Fred Vargas and Ismail Kadare (yes, from French, and not Albanian, into English – he has an interesting piece on what he calls the “Englishing of Kadare” at the Complete Review), and so surely something drawing on his own experience would have been more enlightening about translation as a whole.

Lastly, about the title: I kept thinking it must be some vague attempt at humour, a deliberately poor English translation of one or other expression in another language, although it couldn’t have been French (but that in turn was bizarre since he translates from French, so why would he choose another language?…). As it turns out, it’s an inside joke for fans of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, in which a “Babel fish” is apparently an artificial device put in one’s ear to provide instantaneous translations. So there you have it – although I don’t really see the point of choosing a device that practices interpretation for the title of a book on translation… Soit, as they say.

E-Culture Fair 2011

The second and last day of the 2011 edition of the E-Culture Fair took place today, 17 November, in the Ethias Arena in Hasselt in Flanders. Organized by BAM (Flemish institute for visual, audiovisual and media art), the Flanders Music Centre, the VAi (Flemish Architecture Institute), and the VTi (Flemish Theatre Institute) in collaboration with the Flemish government, the event focused on highlighting the increasing interconnectedness of the fields of culture, creativity, research and technology. In doing so, it offered visitors a glimpse of what the (very near) future will look like. I took care of the translations from Dutch into English of the introductory texts in the catalogue (pictured below) as well as some proofreading of material related to the fair.

Brian Friel’s Translations

Translation is not an intrinsically political field, but like so many other things, from food to clothing, it can be. Translations, by the playwright Brian Friel, is a wonderful example of how politically and culturally charged translation can be. The play is set in the 1830s in an Irish-speaking area in County Donegal. Enter a detachment of Royal Engineers, who are making the first Ordnance Survey and have to translate the local Gaelic names into English. As the blurb rightly says, Friel “reveals the far-reaching personal and cultural effects of an action which is at first sight purely administrative”. First performed in 1980, the play was published by Faber and Faber in 1981 (paperback cover pictured below). For that matter, if you’re in Brussels and would like to see a play in English, then the English-Language Theatre in Brussels website has all the information you need about companies and performances.

Nadja in French, and Nadja in English

It is a well-known fact of course that something gets lost when you read a work in translation, but sometimes the loss can be greater than expected. Take André Breton’s Nadja, for instance. To the best of my knowledge, the only English translation available is the one by Richard Howard. It was initially published in 1960 and is still published today by, I think, at least two publishers: Penguin and Atlantic Books. The Penguin edition (pictured below right) dates from 1999 and includes an introduction by Mark Polizzotti. Howard’s translation, however, is of the first edition of Nadja, which was published in 1928, long before Breton brought out his second, revised edition in 1964. Strangely enough, this fact is not mentioned on the front or back covers of the Penguin edition, although Polizzotti does mention it in his introduction, albeit in a footnote. I haven’t ever read the two works closely, but the second edition notably includes an “avant-dire”, a preface of sorts, in which Breton evokes his use of photographic illustrations in the book, of which there are indeed more in the later edition.

The Craft of Translation

Edited by John Biguenet and Rainer Schulte, The Craft of Translation is a collection of essays on literary translation that covers a wide range of texts (theatre, fiction, poetry, epic) over a long period of time (from the eleventh to the twentieth centuries) and a no less vast range of countries (from South America to Japan).

The essays were all written by literary translators who have tackled major writers past and present, and although not all their names may be familiar, some at least are worth mentioning alongside some of the authors they have worked on: Gregory Rabassa – Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargos Llosa, Juan Goytisolo; Margaret Sayers Peden – Isabel Allende, Octavio Paz, Carlos Fuentes; Donald Frame – Voltaire and Molière; William Weaver – Italo Calvino, Alberto Moravia, Primo Levi; Christopher Middleton – Goethe, Nietzsche, Robert Walser, Paul Celan; Edward Seidensticker – Lady Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji.

The volume is interesting because it gives a quite detailed and well-illustrated overview of the translation process in practice. And indeed, despite the differences in genre and source language, the volume is quite coherent, since all these translators face a number of similar problems, such as how to convey the sounds of a particular language, or how to translate curses and oaths, or how to render local expression and idiom in English. The risks involved in collaborative translations are also evoked by one essayist, who notes that his Americanisms did not mix well with the Britishisms of his fellow translator. The question is also raised by a translator of poetry as to whether his voice should show or, on the contrary, be mute. This issue ties in with the question as to the extent to which the translator should retain a sense of differentness in his translation. Last but not least, the very issue of translatability is raised repeatedly: while one essayist calculates the relative feasibility of a translation before starting on a job, another suggests that the translation of a poem should always be followed by a blank page for the ideal translation, which, of course, always remains out of reach.

Published in 1989 by the University of Chicago Press in their series “Guides to Writing, Editing and Publishing”, this volume is labelled “Reference / Literary Criticism”, and quite rightly so. Indeed, it emerges clearly from these essays that these translators are engaged in literary interpretation that is far from superficial, and their readings of the original works can teach us much.

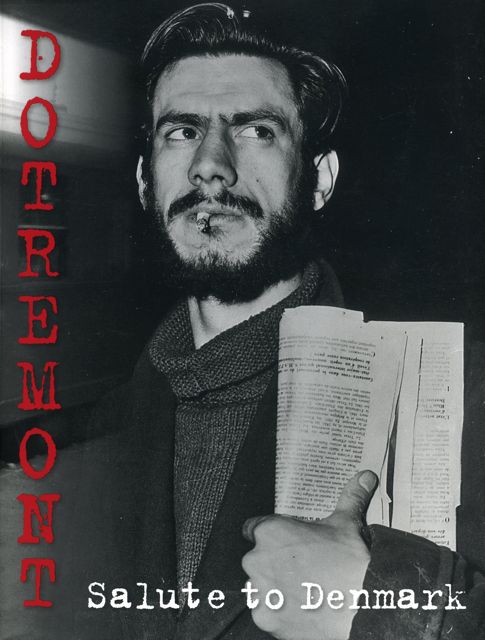

Christian Dotremont’s Salute to Denmark

An exhibition on the work of the Belgian poet and artist Christian Dotremont (1922-1979) opens today, 28 October 2011, at the Carl-Henning Pedersen & Else Alfelts Museum in Herning, Denmark. Dotremont, one of the founders of Cobra and the driving force behind the group, was drawn to Denmark from a very young age and visited the country many times during his lifetime. He first went there in 1948 with the Danish painter Asger Jorn, with whom he created the first word-paintings. Dotremont would later create his famous logograms.

The exhibition runs until 26 February 2012. The catalogue, pictured below, includes my translations (from French) of the article “Dotremont in the Land of Nja” and of the biography. I also translated titles of his works and other short texts used in the exhibition.

Five variations on Don Quixote’s opening line

No two translations are ever the same. Even if you were to ask one and the same translator to work on the same text twice, he or she would most likely make different choices the second time, resulting in a more or less different text.

In much the same vein, different translators working on the same text will produce different translations, no matter how straightforward that text might seem to be. This will be all the more so when the different translators are from different eras.

As an example, here are five translations of the opening line of the “Author’s preface” to Cervantes’s unsurpassable Don Quixote, published in two parts in 1605 and 1615. These translations are from the early seventeenth, the mid eighteenth, the late nineteenth, the late twentieth, and the early twenty-first centuries. I’ve highlighted the various parts of the sentence to make the comparison stand out more, and to show how virtually every part of the sentence is subject to change.

Thomas Shelton’s translation of the first part of Don Quixote was, according to Wikipedia, the first to be published in any language. It appeared in 1612, and it is available on Bartleby:

“Thou mayst believe me, gentle reader, without swearing, that I could willingly desire this book (as a child of my understanding) to be the most beautiful, gallant, and discreet that might possibly be imagined”.

Although Charles Jarvis’s translation was first published in 1742, it is still available in the Oxford World’s Classics series (pictured below left):

“You may believe me without an oath, gentle reader, that I wish this book, as the child of my brain, were the most beautiful, the most sprightly, and the most ingenious, that can be imagined”.

The translation by John Ormsby (1829-1895) was published in 1885, and is currently available on Project Gutenberg:

“Idle reader: thou mayest believe me without any oath that I would this book, as it is the child of my brain, were the fairest, gayest, and cleverest that could be imagined”.

John Rutherford’s version was published by Penguin in 2000, and revised in 2001 and 2003 (pictured below centre):

“Idle reader: I don’t have to swear any oaths to persuade you that I should like this book, since it is the son of my brain, to be the most beautiful, elegant and intelligent book imaginable”.

Secker and Warburg released Edith Grossman’s translation in 2003 (pictured below right):

“Idle reader: Without my swearing to it, you can believe that I would like this book, the child of my understanding, to be the most beautiful, the most brilliant, and the most discreet that anyone could imagine”.

If anything, these variations on the original make me wonder, not so much about what Cervantes meant, but how he would have formulated it had he written in English. But just as that is an impossibility, neither can there be such a thing as an “ideal” English translation (or in any other language, for that matter). And so I’d like to finish off with the original opening line from the Primera parte del ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha (from the online edition available at the Centro Virtual Cervantes):

“Desocupado lector: sin juramento me podrás creerque quisiera que este libro, como hijo del entendimiento, fuera el más hermoso, el más gallardo y más discreto que pudiera imaginarse“.

J.M. Coetzee, writer and translator

I think it’s fair to say that the (two-time) Booker Prize-winner and (one-time) Nobel Prize-winner J.M. Coetzee is better known for his novels and essays than for his translations. In fact, I’m not even really sure I knew that Coetzee had done some translations until I discovered one of these works quite by a chance in a second-hand bookshop some time ago.

The book in question is A Posthumous Confession, a translation – “from the Netherlandic”, readers are told – of Een nagelaten bekentenis (1896), by the Dutch novelist Marcellus Emants (1848-1923). Coetzee’s translation was released in 1975 as volume 7 in the quaintly named “Library of Netherlandic Literature” edited by the no less quaintly named Egbert Krispyn and published by Twayne: Coetzee’s name is visible in the bottom right-hand corner of the front cover (pictured below left). By a strange coincidence, I see that the novel was reissued earlier this year by New York Review Books, with an introduction by Coetzee, dating, however, from the mid eighties (pictured below right).

A Posthumous Confession is not Coetzee’s only translation. He has also translated from Afrikaans The Expedition to the Baobab Tree by Wilma Stockenström: it was first published by Jonathan Ball in Johannesburg in 1983 and by Faber in London in 1984. It was reissued by the South African publisher Human & Rousseau in March of last year. And in 2003, Coetzee brought out a volume of Dutch poetry, Landscape with Rowers: Poetry from the Netherlands, in a bilingual edition published by Princeton University Press.

For readers who are well acquainted with Coetzee’s fiction and who have enough knowledge of Dutch (and perhaps Afrikaans) to read these works in the original, it must be interesting to go over his translations to try to discover stylistic and perhaps thematic overlappings between his own work as a novelist and the works he chose to translate. Indeed, more so than in any other type of translation, here readers really are left wondering who they are in fact reading, whose voice it is they are listening to, whether that of the original author, or that of the translator.

The art of “artspeak” and “artspoke” (but not in French)

There are times when, as a translator, you have to recognize that certain terms or expressions just cannot be translated from one language into another. And I think it takes a good translator to know when to throw in the towel. Here’s an example from an English to French translation.

The American writer, art historian and journalist Robert Atkins is the author, among others, of two useful guides to the field of art and art history and to the field’s particular lingo or jargon. The first of these volumes, published in 1993, was titled ArtSpoke: A Guide to Modern Ideas, Movements and Buzzwords, 1848-1944, while the second, published in 1997, was titled ArtSpeak: A Guide to Contemporary Ideas, Movements and Buzzwords, 1945 to the Present.

The difficulty for a translator in this case, of course, lies in translating “artspoke” and “artspeak”. “Art-spoke” is the simple past, as it were, of “art-speak”, and the term can only really exist, and be understood, in relation to the latter. “Artspeak” was formed, it seems, on the pattern of “Newspeak”, the artificial language used in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. “Artspeak”, then, hints at the impenetrable obscurity of this critical jargon while also promising, as the title of the volume, to shed light on it.

So how is one to translate these terms into French? Well, one possibility, for “artspeak”, would be to do so on the pattern of the French translation of “Newspeak” (the dreadful “novlangue”). But “art-langue” or something similar would not only be meaningless but also sounds quite ridiculous, besides failing to capture the contrived nature of the term. Needless to say, conjugating that term to arrive at an equivalent of “art-spoke” seems virtually impossible.

The translator of these volumes, Jeanne Bouniort, thus rightly chose to drop “Artspoke” and “Artspeak” from the titles, and to opt for broader, though also more concise titles: Petit lexique de l’art moderne, 1848-1945 (2000), and Petit lexique de l’art contemporain (1998). And in fact, the French editions are presented as French “versions” of the English text, and quite rightly so, too. Both the English and French editions are published by Abbeville Press, which specializes in fine art and illustrated books.